Historical class conflicts

The field of economics used to be called political economy. There was a reason for this. At the time the field was first formed the interaction between classes of people was considered a fundamental part of economics, and class conflict was usually a political fight over scarce resources.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, economists, many of them French, began to work out the mechanisms of trade or commerce. These guys came up with notions of “supply and demand,” “labor value,” and “pricing”. The earliest political economists also made attempts to define human nature, with most taking the Christian position that human beings are innately sinful. The main conflict that they focused on in the rising age of global shipping (via the East Indies Company) was that between “buyers” and “sellers”.

In the 18th century it was Adam Smith’s genius that he managed to incorporate this notion of imperfect human nature into political economy in a way that completely sidestepped the implications of human fallibility for possible conflict between the two classes called “buyers” and “sellers”. Smith deduced that there had to exist an “invisible hand” (of God) that somehow operated whenever people pursued their own pleasure, or as economists called it later, “utility”, when buying and selling to each other. As a result of Smith’s “invisible hand” device, the combined self-interested activities of each person would be smoothed out through the mechanism of the free marketplace, and any original sins of all the participants would be negated.

Smith’s contemporaries, including clergy, didn’t buy that assertion. The doctrine of original sin of mankind gave impetus to the view held by other political economists that classes of people would be bound to have conflicts because most human beings are not self-sacrificing altruists. Among the earliest conflicts observed by political economists was the inherent conflict between (land) lords (those who owned agricultural land and structures on those lands) and their tenants (those who were renters and worked the land).

The writer who made the class conflict between landlords and tenants notorious was the Dean of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin, Ireland. Jonathan Swift became enraged by the results of high rents and poorhouses he saw in Ireland. in 1729 Swift wrote the classic tract, “A Modest Proposal for Preventing the Children of Poor People From Being a Burden on Their Parents or Country, and Making Them Beneficial to the Publick”. The public was horrified by Swift’s proposal that babies of the poor be eaten by the more affluent Irish.

In 1798 the Reverend Thomas Robert Malthus suggested that in our pursuit of self-interest, we would all wind up starving to death because of the “law of diminishing returns”. Mathus thought that human beings would create a bigger population than the earth could feed. Because of Malthus, economics is still called “the dismal science”.

After the industrial revolution made it possible for almost anyone to publish a book, an impoverished newspaperman exiled from Germany, Karl Heinrich Marx, began writing books at the British Museum in London in the mid-1800’s about the brand new kind of class conflict. This was the urban conflict between workers at and owners of a new type of private property called “factories,” used for manufacturing goods.

Modern class conflict

Modern economics, with its dictum that economics is a social science and not a political science anymore, dropped the notion of class conflict after Karl Marx came out with his highly political books about political economy. No one in modern economics today seems to be talking much about class conflict. Even the Occupy movement has chosen to brand itself as the 99% majority rather than as a “class”. And as you’ll see in the section on the Attica prison revolt below, that makes sense now that we have an incredibly small number of extremely wealthy people in the world called “billionaires“.

While working as a volunteer in the 1970s for the National Welfare Rights Organization (NWRO) during my graduate school days in Economics, I was confronted by the reality of class conflict in America. I saw close up and personally that it is the job of a large part of the “middle class” to take care of those who are in the “underclass” called “the poor.”

These paid caretakers include police, social workers, public hospital workers, public school teachers, public library librarians, and government bureaucrats among many others. The assumption of many middle-class workers make is that they are “doing good”. This is why they get into these positions where they work with poor people. They want to do the right thing for those “less fortunate” than they are.

But my observations at the NWRO were that social workers were doing anything but looking after the true interests of the poor. The law in Wisconsin at that time said welfare mothers could receive only 95% of need from the state. What about the other 5%? Social workers made home visits and kept an eagle eye out to make sure the mothers weren’t getting any help from others (including “men friends”) that might make up for that 5% difference.

I watched as welfare mothers were denied refrigerators that worked, glasses for their children, and even working elevators in large apartment buildings in Milwaukee, where children played in the halls and were in danger of falling into the elevator shafts. In short, welfare workers’ jobs were to parse out as little money as they could to the poor while making a nice salary themselves for doing that.

Watching the welfare mothers cope with the patronizing view of them held by those who “helped” them and how these mothers still managed to take care of their children, I was impressed. One of these women, activist, author, and political adviser, Maureen Arcand, a woman with cerebral palsy and six children, even came to have a public park (Arcand Park) in the capitol of Wisconsin, Madison, named after her.

These women had to stand up to “power” constantly and assert their own truth. When the legislature became deadlocked on the the budget that year, I joked that the mothers should be brought in as consultants to help the legislators get their finances back on track. Only the mothers seemed to know how to survive on a budget based on 95% of need.

The meaning of the Attica revolt

The year I was a volunteer at the NWRO office (which was staffed by activists paid a salary by the federal government’s Vista, Volunteers in Service to America program), an event took place at Attica prison that was news across the the entire United States. Earlier there had been riots in American cities. Attica was the first riot at an American prison to be broadcast on national TV news in the US.

Nevertheless, most of us who lived at that time did not know the real story of the grisly murders at Attica because that story was covered up. It was covered up by the middle-class employees whose job it was to take care of the prison underclass. These were New York State Troopers and prison guards at Attica. Then it was further covered up by New York State politicians who had a lot to lose if the truth became known.

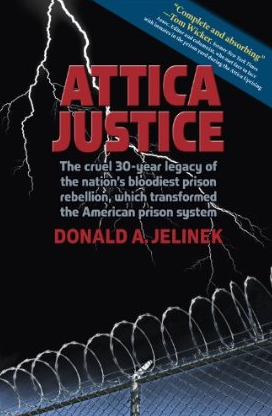

Donald A. Jelinek, the attorney brought in to coordinate the defense of Attica prisoners after the riot ended, has written a compelling account based on eyewitnesses records of the events at Attica prison during the five days the prisoners took over the prison to demand better living conditions. Jelinek’s book is called Attica Justice: The Cruel 30-year legacy of the nation’s bloodiest prison rebellion, which transformed the American Prison System. (Disclosure: I was asked for advice about using a computer software program to create the index for this book.)

In Part II, as Don Jelinek covers his own role as at the leader of the defense for the prisoners and the legal maneuvering that takes place, he gradually reveals the existence of the cover-up of what happened at Attica and how the cover-up ultimately unraveled, taking with it the political careers of prosecutors and ultimately that of the Vice President of the United States.

But it’s in Part III of this documented “thriller” that the truth of social class in America is revealed. The surviving guards who were taken hostage at the prison, and the widows of the guard/hostages killed when the prison was re-taken by their colleagues, were the ones who lost as much, perhaps even more, than the prisoners. Although this isn’t always the case for members of the middle class, what happened at Attica is a warning for all of us. As this book shows, any member of the middle-class can be cast down into the ranks of the poor at any time during their lives.

Yet many in the middle class take for granted their rewards for taking care of their own class’s needs and/or those of the underclass(es) they work with. The middle class often views the poor as utterly incapable of taking care of themselves rather than seeing the poor as the unfortunate losers in a rigged game of “musical chairs”. Many members of the middle class also wrongly believe that the poor need the middle class to take care of them, when in fact what the poor actually need is more opportunities to make money.

Attica showed that the rewards given to middle-class gatekeepers could be cruelly taken away by highly-paid bureaucrats, the “upper-middle-class” managers, who are themselves paid by those above them to see that middle class people don’t get 100% of what they need either. This chain of privilege and power, along with the deprivation and denigration of those with lesser socio-economic status than oneself, goes all the way up the chain to the top where the “buck,” by definition, finally stops with the billionaires, the 1%.

If you were alive in 1970, you’ll recognize many of the famous persons who took part in the Attica drama. If you’re in the upper-middle class, middle class or among the poor, you’ll see exactly what could happen to you when such a situation happens again, as it surely will from time to time in a society built on a finely stratified hierarchy of class conflict that no one, most especially not most economists, wants to acknowledge exists.

Follow Nancy Humphreys on Twitter @brucenomics and Become a Fan at HuffingtonPost

2 comments ↓

After reading your post, Nancy, everyone should watch Rachel Maddow’s interview with EJ Dionne about his new book.

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/26315908/

I learned the difference between political economy and economic policy from your article. Thank you. Very informative and interesting. Economics is such a broad subject. I enjoyed political science in college. In your other post you made a good comparison of monopoly/oligopoly pricing with your NBA pass example.